News Editor Colin Mitchell sat down with Dr. Rick Mehta on Friday January 12th to discuss recent remarks made in various media outlets. The Athenaeum in no way endorses or sanctions the views expressed in the article below.

First off, what do you see as the main issue with the things you’ve said and the backlash you have received regarding indigenous peoples and the letter you sent to Andrew Scheer?

So basically, the attack was not on the people but on the decolonization movement. That’s a very different issue. There’s decolonization vs. the people. In terms of the decolonization, its proponents are people who are claiming, you know, they claim to be community leaders, but are not people who have been elected to that position. It’s people who are claiming to represent their entire community but people who are self-selected. They differ from the majority of their community in the sense that they’re going to be much more highly educated than people who don’t have access to clean drinking water, as an example. These are things they can take for granted. They’re in a financially better situation, more highly educated and tend to be urban and have better access to resources, so they’re not in a position to claim that they’re true representatives of their community. It has to do with the framework under which the decolonization is occurring.

What is your opposition to the decolonization movement?

It’s based on a premise of guilt. Instilling guilt into the non-indigenous people, so anyone who dares to question their motives or what their- I hate to say demands- but basically what they want to institute is just ignored or they’re going to be called racists. The fact that they’re suppressing debate, which is the kind of action someone would perform if they don’t wish to be scrutinized. If the TRC was truly about truth, the idea that there are lots of stories of people who had positive experiences would still be there. I got a phone call from a lady whose name I wish I’d written down, but-

Just to clarify, you’re saying that there are lots of stories of people who had positive experiences in residential schools?

Exactly. With the one woman who worked in the system, she told me it originated in Sault St. Marie by a chief who had requested it. He wanted it because it was the new way of living so he wanted his people to adapt. So that’s one major issue. The other point she mentioned, which I hadn’t thought about, was look at the new $10 bill. Look at the individuals on it. One of them, if you do your homework, is someone who was from the residential schools and was a successful figure. That really counters the narrative. I’m not at all opposed to acknowledging atrocities, but it is within the context of the entire picture.

You claim that the TRC was a biased process because it didn’t take all views into account. There were over 6750 statements collected, 1355 hours of interviews, and 7 national events. Which views are missing?

We need to look at the details of who was actually selected for the process. How representative was that sample? Was it a biased sample? Or was it a representative sample? Let’s say Tomson Highway, he talked about 7000 people who had a wonderful experience. I’ve received letters now from another individual who’s trying to get their voices heard.

Senator Beyak defended the “good deeds” by “well intentioned” religious teachers in residential schools. With nearly 150,000 students who passed through and over 31,000 sexual assault claims made through independent assessment processes, can you really defend the good intentions of those in charge?

We need to look at the comparison of what was happening in society at the time. There’s what’s happening within indigenous communities, but attitudes about what was happening towards abuses at homes in general would be the other side. In terms of our history, and how we dealt with those issues was very different from how we deal with those now. Whatever happened within those schools and other schools that was considered acceptable is a relevant comparison that needs to be made to get a full picture.

Are you saying that the acceptability of sexual assault is relative in terms of how it was received at different points in time? That it was more acceptable then than it is now?

I mean, partly awareness, and how we dealt with it. The culture has changed quite dramatically over the times. If we’re doing that analysis it needs to be with the full picture and within the context of what was going on at the time and what was considered acceptable then vs. now.

You wrote in your letter to Andrew Scheer that multiculturalism needs to end. Why?

It’s a way of separating the world into us vs. them. Instead of looking at our commonalities and then trying to sort out our differences, the way it’s marketed is ‘we must not only acknowledge we’re different but celebrate our differences’. But those differences don’t always mesh together for ways that are functional in Western society. I’ll give the example of what happened to me when I was an undergrad in my first years of university. At the University of Toronto I was a first generation East Indian Canadian. This was when multiculturalism was starting its first wave under the Mulroney years, and I’m there as a student. I thought I’d join the Indian Students Association. I noticed that the males would filter who their sisters could date, so if someone wants to date a girl they’d have to get permission from their male relative. When I voiced opposition and said that women were more than capable of choosing who they wanted to go out with, I was called various names. The one that stuck was “Oreo Cookie”- brown on the outside, white within. Canada’s placed on the premise that men and women are equal when it comes to dignity, so when the issue of whether women should be equal to men in all ways or not came to me, I thought it was more important than the cultural value of being an East Indian. That comes to the question of are we going to have a conversation about our values? You can’t have that conversation under the framework of multiculturalism. There has to be the idea that Canada has its identity, these are the kinds of goals we strive towards, but try to have bit of flexibility. The old was ‘live our way or get out’ and I think that’s a bit harsh. I don’t think we have to go back to that extreme.

Just to clarify, your method of thinking is that everyone should be on the same playing field?

The way I see it is you’re driving on a highway and we all have similar rules. We have a way to express ourselves in terms of what kind of car you’re driving, what colour it is, what style. There’s room for self-expression but there needs to be a certain set of fundamental principles we agree on- you drive on the right side, you drive at certain speeds, which is different from a highway than a subdivision where there’ll be pedestrians and children. There have to be some areas where we have agreement and flexibility, but there have to be some rules and core values we adhere to. Within that, here’s ways that you can express yourself and express our differences.

Beforehand you mentioned you were opposed to an us vs. them dynamic, but earlier you said that people need to adapt to Western society. Is that not a logical contradiction?

It’s the idea that in certain places there’ll be less flexibility vs. others. Like food, for instance. Someone should be able to bring their food into the lunch room and not have people turn their noses at it and call them names for it. That I would consider less acceptable, but then it comes to core principles like equality of the sexes between men and women. There we cannot have a workplace where I can treat women like dirt because of my culture. We need to have a discussion because we need to fine-tune and I’m trying to figure out where do we have more flexibility as opposed to less flexibility

What is your opposition to the university right now? Where does the major contention lie?

One major issue is equity. It’s based on equality of outcome, as opposed to equality of opportunity. I’m all for making sure that everyone has the opportunity to be treated equally so they’re not discriminated against based on criteria that are irrelevant to the jobs. But to have equal outcomes and to define society in a specific way if its distribution isn’t reflected in the workforce, that the disparity there in and of itself is a problem without actually looking for reasons why. There are differences in the kinds of careers women choose over men. What you have to keep in mind is that these are just averages. The nuance needs to be there. I’m not saying ‘all women are this or that’, but on average what do we see when we compare men and women in their interests, so the idea is when it comes to individual differences there are going to be averages. But you still then need to look at the individual because we don’t know where they are in relation to that average. On average, men tend to prefer working with things whereas women on average tend to prefer working with people. But in terms of the exception you just have to look within my family. I just love working with people. That’s why I love doing first year psychology, because I thrive around people. I don’t mind being in a department that’s dominated by women. It doesn’t bother me the least bit. My mother, who was the computer programmer and became a senior systems analyst, who I think could be at Google, is the one telling me I should apply for the full professorship and make more money, but I’m more in line with the female average, which is I’m making money and I’m more than comfortable where I am as opposed to getting the promotion.

You refer to an incident that happened two and a half years ago. Can you tell me a bit about that?

Basically, it was a couple of incidents where I realized I was part of the problem where I thought I was the one advocating for tolerance when I myself was intolerant. I can give you two incidents. One was when I was talking with a friend of mine, who was a key role in pushing me over to the left, basically saying that everything was the fault of the military industrial complex or Stephen Harper. The examples he gave are obesity rates in Canada. I don’t see at all how those are related to Stephen Harper or the military industrial complex. Even within my own subdivision, why people didn’t want streetlights or sidewalks, and when I told him that people wouldn’t want their property taxes to go up that was just dismissed. There was that, and the other was during the time of the Canadian election. These are the facts that you can empirically verify. Being in the university environment, where we’re all anti-Harper for the most part, I was angry for how Tony Clement spent money on gazebos in his riding. I can’t remember what date it was, but he rescued one of his constituents at the beach. Tony Clement rescued him and I was unwilling to give him the benefit of the doubt as a human being for having done that. I then realized that was horrible for not being able to separate the deed of the politician from the deed of the person. How can I say that I’m going around as a liberal advocating for tolerance? Those were some of the turning points where I started questioning myself and stick to my core sets of values- what I believe and why I believe them. I don’t need it tied to my identity as a leftist or liberal. I just want to discuss them in a way that leads to consensus.

How would you describe your political leanings? In the past you’ve described yourself as a civil libertarian, but what exactly does that mean? How would you unpack that?

We generally have our rights and freedoms and ways of respecting each other, as well as the idea that we have certain sets of commonalities. That gives us a framework so we can talk to each other as human beings. Within that framework we can look at our differences, some that can be solved in the short and some in the long term. Asking how can we put those in a hierarchy so we can arrange our problems so we can differentiate between the ones that are more easily solved compared to the ones that are going to take a bit longer, and just work our way from the bottom to the top? It’s built on a notion of trust and that we’re constantly communicating with each other. Short term vs. long term.

You’ve mentioned a lot of your discontent with the academy deals with their methods of thinking. Do you find that thinking within the university is more focused on the short-term than the long term?

It’s definitely gone towards short term gains without thinking at all about the long-term picture. It’s become much more insular here, focused around ourselves and not even about what I think is the university’s constituents, which is Canadian society. How do we actually relate to our Canadian society? My employer is not the university, but the Canadian public because in terms of who pays me at the end of the day, it’s the average Canadian. Every time they fill out their tax form, go to the store, pay that HST, that money gets to the government, the government funnels it to the university, who funnels it to me. The other employer is my students. Not in the sense of they pay the tuition and I give them marks, but the fact that students have paid a tuition with the ultimate goal of their education being that I’ll teach them to think for themselves based on facts and being a good consumer based on those facts so they can formulate their own world view and then articulate themselves so they can convince them to adopt their point of view or see what’s correct and adopt their view. It’s not up to me to tell students what the right thing to do is, but to give students the information and let them figure it out and discuss it amongst themselves.

Do you think that it’s appropriate for the classroom to be a place to discuss what some might perceive as offensive topics?

This is definitely the place for contentious issues. If you can’t discuss contentious issues at a university, then where can you? The fact that we’ve been asking that question-

I don’t disagree, but there are students who feel that you’ve brought your own political leanings into the classroom this semester.

My main problem is the university is divided politically. The divide between people who are of liberal and far left to conservative and middle of the road dispositions has become so extreme that there are whole sides of the equation that aren’t even discussed. It’s like ‘Ok, here’s what you’re hearing in some courses so you already know this perspective, here’s another perspective to consider’. That’s very different. I’m exposing them to different sets of ideas and they have to determine for themselves what they think.

Could some of those ideas be hurtful to students? The one question I have is what you would say to an indigenous student in your class noting that you retweeted a post on Twitter discussing the ‘aboriginal industry agenda’, which was to claim that indigenous peoples are ‘playing the helpless victim’ to ‘simply cash government cheques’ and called it all a ‘scam’?

That was for the industry as opposed to the industry, as opposed to the individuals, which is why I stand by that retweet.

Can you elaborate?

Like I said before, it’s a group of individuals who claim they’re speaking for their group. My key criticism is that they’re assuming all members are exactly the same so there can’t be an indigenous person who supports the oil sands, or maybe who is an atheist, or maybe an indigenous person who’s a Muslim. It’s based on a specific stereotype which is based on connection to the land. That’s one kind of a stereotype, but there are very different points of view. They might be conservatives, they might be libertarians, there’s no one homogenous groups. In terms of what I call the industry, this one specific view of an aboriginal is what I mean, and those other voices that aren’t being heard are the ones who need to be criticized. Not me, because I want to hear the different perspectives. I’m not treating them all as a group, I’m treating them all as individuals. My critique of the retweet was the specific people claiming to be leaders.

But as of 2016, 60% of indigenous children on reserves live in poverty. Over 140 drinking water advisories are in place on reserves across Canada. Don’t the people who are bringing those issues to light have a place in doing so, even if they’re not speaking for the other 40% of indigenous children who are not living in poverty?

The way I see it, they’ve been leaders of their communities for how many years. What changes have they brought? What improvements have been brought? We keep hearing about how the problems are there, but the question I have is why are they still persisting after all these years? How have there still been no improvements? We put our money to use to make these things happen, but where is it really going? When there’s an act like the First Nations Transparency Act, the first thing the Liberal government did was take it away. In the meantime, look at Charmaine Stick. Within her community the leaders have taken money and she can’t get accountability for her leaders. She’s working with the Canadian Taxpayers Federation to take them to court. There are problems where what’s happening in the communities is quite dysfunctional, and I don’t hear a word from any of our leaders saying that the people we see on TV, who are claiming to be in these offices of indigenous leadership, I haven’t heard them speaking for people who are indeed in poverty or transparency within their own communities.

What is your definition of free speech and hate speech?

Free speech is saying the ideas that are on your mind. Your views on any issue. Hate speech is what is in the law. Anything related to the defamation of character or advocating for someone’s death. Hate speech is unique to Canada because it’s not even an issue within the United States. There they’d say hate speech is protected speech. The main problem with having legislation with hate speech is that it can always grow. In terms of what happens under the guise of inclusion, whoever is the person being offended is the one who gets to dictate the discourse that happens in the classroom or society. We can’t have that happen because then nothing will be discussed.

A large issue around free speech is at what point does it become hate speech, and at what point is society justified in restricting it?

Well, the whole idea of hate speech is something recent in terms of the public discourse-

Is it? If you go back to the 1950s and 1960s in the southern United States, you have white people calling African Americans incredibly offensive names and advocating for lynch mobs. Isn’t that hate speech?

There you’re actually advocating for someone’s death, so that would be, but this isn’t something that happens in the classroom. That’s not typical for everyday discourse and not considered acceptable. How often do you have a classroom setting where someone is advocating for another’s death? That seems like a non-issue, and the fact that we’re bringing that up is disappointing. If you’re doing something like slandering someone, that’s not hate speech. Let’s use Gad Saad. He’s someone who escaped Lebanon as a Jew, came to Canada escaping persecution, and he’s more than welcome to let people deny the Holocaust because they’re more than welcome to their ignorance. For me, I don’t mind if someone says to me I’d be better off living in India under British rule. That’s just their position, I don’t see that as hate speech, so long as they’re not advocating for my death or slandering me any way. Hate speech is an outright act where people can objectively see it, but the general idea that we shouldn’t have issues based on hurt feelings. Ultimately we’re going to get offended. What offends one person might not offend someone else. Mere offence of itself is not of itself hate speech. You have to look at the intention too. If I crack a joke that’s meant to purposely make fun of somebody based on their sex or whatever, that’s very different from somebody saying ‘Well, within my East Indian community rates of domestic abuse and selective abortion are going to be higher’. Bringing those up doesn’t make somebody racist because it happened to hurt my feelings. Hurt feelings, in and of themselves, without looking at the intention behind them.

There was a debate in the Oxford Union discussing the right to offend, where the proposition argued that it helps to advance society. If one was to say in the late 1800s that a man should be able to have sex with another man, it would offend people. The central point of the argument was allowing people to offend has allowed society to progress, but at what point does society become justified in restraining certain kinds of speech?

Only when somebody is advocating for death or physical harm. It needs to be very, very restricted. Under very restrictive circumstances, otherwise you can’t have discussions. I can give the example of the gay community. In high school, in Grade 12 law, our teacher presented the example of a marriage that’s fallen apart, where the woman can’t hold a job, is addicted to drugs, and has a different partner every day. The male, perfect in every way, has a job, security, a good house, but the reason for the breakup was that he was a closeted gay. The question became who should get the child. I was sitting at the very front of the class and I raised my hand for the male, and then I turned around and it turned out I was the only one with my hand up. I was curious about why that would be, but it was homophobia. They thought that if the child goes to the dad it would be bad because he’d be a bad role model because he’s gay and that children shouldn’t be exposed to gay people. That was one argument that was given, and that the child might become gay. These were some arguments given, and back then there was nothing covered in our classes about what a gay person was. I thought they were these fictitious people who lived out in Vancouver because I’d never met people who were gay. I didn’t even know there were people in my class who were gay. With that class debate, it was me vs. the rest of the class. Where there was open discrimination I was the one voicing dissent. I remember someone saying ‘Oh yeah you probably think they should get married too’ and then laughing. In retrospect, I stand by every word I said then just like I stand by every word I say now. Back then I think I was right on the right side of history, and I think I am now too. I’m getting support from people who were in residential schools themselves.

Really?

Oh yes, I would show you but I want to respect their privacy.

My last question is that normally we would not defend somebody who said that the Holocaust didn’t occur, and would restrict their right to espouse those views rather than hold them. Do you think your comments on decolonization and residential schools reach that threshold?

I will agree with Gad Saad. If someone who escaped religious persecution can say ‘You guys are entitled to your ignorance and can spout that’, then I’m fine with it. The reason I want them to say it is that in a classroom setting it can be challenged. You can find a way to challenge it, and you can do it discretely, but you can have a conversation and realize why one is right or wrong about it. If you can do it in a classroom setting where you can separate your emotions it becomes a learning opportunity because you can prove people wrong. This other example I use is where somebody grows up in a community thinking that all gays are evil and an abomination, so it’s welcome. We can challenge one another and have a conversation, because you don’t know why they’re expressing that view on what’s arbitrarily considered hate speech. Understanding where it came from and why that view is held allows somebody to ask why they believe that and where it’s coming from. If we allow people to express views that even seem hateful or hurtful we can them follow up those questions and figure out how to change their mind.

I actually have one more question. Do you expect indigenous students to feel safe or comfortable in your classes, despite some of the comments you’ve made?

Yes because they can challenge me on it. They can come up to me and say ‘I think what you said is bullshit’. I’d rather them be discrete, but I think I’ve been careful on my wording for my posts online. Perhaps not that specific one retweet, but about the community and the specific individuals who are claiming to represent their community.

Dr. Mehta, thank you for your time.

Comments

13 responses to “The Right to Offend: Q&A with Dr. Rick Mehta”

Awesomesauce. Well done Acadia folks.

If I was looking at schools to send my kids to, any school that has a prof like Rick would be at the top of my list. What a breath of fresh air, sounds a lot like of kids are going to be very lucky to take his courses.

Keep it up Rick and Acadia for having these conversations, however painful they might seen in the short term in the long run you’ll be on the right side of history

Send your kids elsewhere. A lot of us students feel discriminated against and degraded. Don’t let your kids feel like that.

Do you believe comfort in your own beliefs is more important than the ability to challenge what you believe is wrong?

If so, why?

Thanks for taking the time to consider what I’ve said.

M, the question isn’t whether you feel discriminated against and degraded, but whether in fact Rick Mehta has discriminated against you or degraded you personally. Has he? Of course he hasn’t. He has challenged you to an honest debate about a social issue, and you don’t have any arguments to defend your point of view, so you retreat into offended victimhood. That is cowardly.

Cause we are in a generation of cry baby’s stop searching for things to hurt your feelings

When AREN’T students offended nowadays? I spent 8 years and two degrees later I never found such an insufferably self righteous, sanctimonious, and ultimately weakminded cohort to challenge so-called “students”. All whining, all bandwagoning, all parroting feel-good-but-achieve-nothing propaganda and speech policing.

I personally studied under Dr. Mehta over a decade ago and found him to be highly intelligent, soft spoken, and a man of integrity. If only his detractors could live a life of equal merit and accomplishments without crying and pointing the finger elsewhere.

Grow up kids and stop kissing ass to your lockstep arts faculty sycophants.

There seems to be a contradiction.

You seem to idolize Mr. Mehta, but you stereotype?

“All whining, all bandwagoning, all parroting…”

Whilst I’m not a student of Mr. Mehta, I do admire him as well. You claim that all students are self-righteous and sanctimonious, but I could make the argument that my lack of offense taken from the shot you just aimed at me and other students proves you wrong.

I don’t believe I’m morally superior to anyone else. I don’t believe I know more or better than anyone else. Quite the contrary. I know so incredulously little.

But isn’t it hypocritical implication to generalize that a group of people are lesser?

Thanks for taking the time to consider what I’ve said.

Dr. Mehta’s key point seems to be that people should be able to discuss difficult issues without the process degenerating into name-calling, especially in a university setting. Being offended is not a good enough reason to turn a civil discourse into a series of personal attacks – your point of view is only as good as your argument supporting it.

I would be more than happy if my children could learn such things from an educator like Dr. Mehta.

Second that Paul..It’s a free world and I have opinions and which may or may not suit others but hello it’s just an opinion don’t take it personally and use it against me.

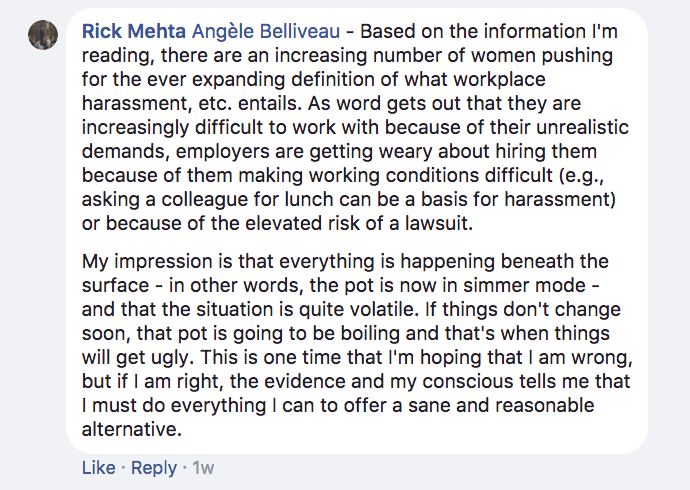

Rick Mehta claims “students with university degrees (women in particular) are likely to be unemployable because they can’t have a civil conversation on a difficult issue without it deteriorating into name calling, namely because they don’t know to even form arguments – much less discuss complex issues.”

Yet in comments above supporting Rick I have seen “insufferably self righteous, sanctimonious, and ultimately weakminded cohort”, “sycophants”, “generation of cry baby’s”, and “cowardly.” “Snowflakes” and “soy boys” are rampant in Facebook comments supporting Rick.

If you’re going to support someone, you might want to consider not participating in what they are arguing against.

Signed,

A female student who is capable of forming an argument.

As Margaret Atwood recently said, “extreme times breed extremists.” We are presently living in extreme times, and this is why we continue to witness the extreme polarization of the left and the right to the point where they have become identical twins in their extreme behavior. In this extreme, the ability to listen, to consider, to think, and to respond rationally and reasonably has stopped–except on the part of the quieter, gentler moderates in the middle, but they are shouted down and condemned from both sides. Ideas, opinions, speculations, opinions, and beliefs must be expressible in a healthy society–except where they advocate for the annihilation of others. Everyone must have the inalienable right to hold and express offensive views. And everyone must have the inalienable right (some might say duty) to respond cogently, to express offense on the spot, and to counter with just arguments. First-year university students are adults, not kids, and need to get used to and learn to deal constructively with issues that push their buttons, make them uncomfortable, or sad, or scared. In order for a young adult to be ready for university, parents need to stop their practice of bubble-wrapping their young in order that they learn to be strong, critical thinking, responsible members of a healthy society, rather than weak, compliant victims of an unhealthy one. Kudos to Rick Mehta for picking his battle and being prepared to deal with the consequences in an intelligent manner. He is at risk of being ostracized by both the left and the right. He is condemned by reactionaries on either side who don’t want to hear or counter his rational arguments. This is the curse of living in extreme, if not interesting, times.

Please see chapter 40, Setting Indians Free From Their Past, at http://www.nodifference.ca, for examples of prominent Indigenous Canadians agreeing with Professor Mehta that some good happened at residential schools.