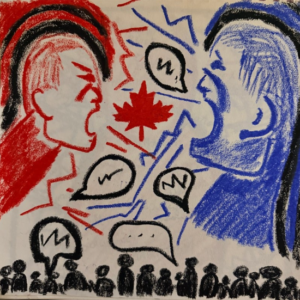

In recent years Canadian democracy has faced an uneasy transformation. Elected institutions, public service providers, and the media, once regarded as the defenses of civil engagement, are now confronting new forms of hostility, online fury, and organized anger. What one might call hatriotism, or hate-rooted patriotism, has surfaced: a form of political participation focused less about building the country and more on attacking those seen as betraying it. This essay argues that hatriotism in Canada is rising through three inter-connected mechanisms: online and offline extremism, rage-farming networks that mobilize anger, and targeted harassment against journalists and public figures – each undermining democratic participation and public trust.

First, the foundations of hatriotism lie in modern online and offline extremism. Historically, the political arena in Canada has been framed as reasonably moderate and consensus based, but that assumption is weakening. Many experts in Canadian politics have highlighted that extremism is no longer something that is “far away,” or only a concern in other, distant countries. A 2022 article from the University of Calgary writes, “Once the headline news of other countries…it seems extremism in politics has finally taken root in Canada.” Additionally, It’s proving hard to eradicate as it garners increasing support. Digital platforms and identity-based grievances can also feed into hatriotism. When political affiliation becomes the defining marker of who one is, rather than what one stands for, polarization deepens. Extremism no longer only means large rallies or overt violence – it means networks of people online who believe the system is corrupt, the government is a traitor, and those who disagree are enemies. These narratives cultivate the hatriotism mindset: “the government is a conspiracy and anyone who thinks otherwise is wrong.”

Second, rage-farming and deliberate provocation are converting frustration into mobilized hatred. The term “rage-farming” describes political actors, frequently on the right, who stoke anger, conspiracy theories and distrust toward public institutions to build a following. In a documented case, the verbal attack on Deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland in 2022 at Grande Prairie has been linked to this phenomenon. A man shouted, “traitor to the country” at Freeland, telling her to “get the fuck out of this province” as well as other verbal abuse. In a later interview, the man cited multiple conspiracy theories around the Trudeau government as the motivation behind his actions. Jared Wesley, an Albertan political scientist, stated that, “aggressive attacks on politicians will increase in Canada as right-wing politicians continue to engage in ‘rage-farming’ by advancing false and misleading conspiracy narratives.” In essence, rage-farming rewrites politics: it becomes less about policy debate and more about dramatizing enemies and grievances. Hatriotism thrives in this environment because it flips the script: patriotic identity is seen as not about protecting the country – but about defending it from perceived internal enemies.

Third, the rise of hatriotism is deeply linked with targeted harassment, especially of women, racialized people, and journalists. This works to effectively dictate who can safely participate in public life. Spoiler: it’s mostly white men in business suits. Online abuse in Canada has surged, particularly after the 2022 Freedom Convoy coverage. A 2025 article from the Review of Journalism noted that following the convoy, online harassment against journalists spiked: “Most of the victims have been women of colour, causing many to consider leaving the industry.” During an interview, Barbara Perry, a professor at Ontario Tech University, stated that gendered online hate is “so intimately intertwined” with far-right extremism that you cannot separate them. She went on to comment that “Women in politics, women in journalism…are more and more subject to…online threats and offline threats.” The implication behind this pattern is terrifying: when participation becomes dangerous for certain groups, democracy becomes less inclusive and less effective. Hatriotism thereby attacks not just institutions but the people representing them. In other words, hatriotism attacks democracy itself.

These combined mechanisms signal several serious issues in Canada’s body politic. First, trust in institutions is declining. When politicians are shouted at, when journalists are threatened, when protests call for the elimination of ‘enemies’ rather than reform of policy, the legitimacy of democratic systems erodes. In fact, the attack on Chrystia Freeland at Grande Prairie was labelled as “an attack on democracy” by the Crown-Indigenous Relations Minister, at the time, Marc Miller. Secondly, participation becomes unequal. Those who can safely engage – usually white businessmen – continue to dominate, while women, racialized people, and marginalized communities are forced to withdraw, walk away or quit. This deepens representation gaps and fosters exclusion. Third, political culture shifts away from reasonable dialogue and moves towards spectacle and confrontation. This can regularly be seen during the Question Period in the House of Commons. For example, Pierre Poilievre was ejected from the Commons during Question Period on May 1st, 2024 after calling the Prime Minister “a wacko,” then offering “radical” or “extremist” instead when asked to withdraw. The rise of identity-based politics and online radicalization means hatriotism is less about “citizen engagement” in the classic sense and more about an ‘us vs. them’ hostility. Finally, the risk of violence increases. When hate becomes normalized and aimed at public-service actors, protests can escalate, institutions can be targeted, and public safety can suffer.

How can Canada quell the rise of hatriotism? After all, the word hate isn’t typically associated with the global reputation Canada enjoys. While an all-encompassing solution is complex, a few steps are clear. The first is improving digital literacy. Citizens must learn to recognize how rage-farming tactics work, how conspiracy content spreads, and how online platforms amplify hostility. We can do this by reinstating the ability to post credible news sources on social media, such as Facebook and Instagram. Additionally, support and protection must be extended to those most threatened by hatriotism. This includes women in politics, racialized journalists, Indigenous activists, and ordinary people who believe in the power of democracy and federalism. Ensuring safe participation for everyone is a democratic priority. Political elites and parties must resist the temptation to feed the rage monster for political gain. Accountability mechanisms and public condemnation of hateful tactics matter in combating hatriotism. Finally, inclusive civic education should emphasize Canadian pride rooted in engagement, dialogue, and institution-building rather than resentment and exclusion.

In conclusion, the rise of hatriotism in Canada signals a turning point: politics is no longer just about choosing governments, managing rights, or balancing federal-provincial relations. It is about the emotional fuel of anger, the spread of digital hatred, and the targeting of those who represent the system, often by those within the system. By recognizing the mechanisms of hatriotism – online extremism, rage-farming, targeted harassment – we open the possibility of reclaiming a healthier democratic culture: one defined by participation, trust, and inclusive engagement rather than resentment, fear and exclusion. For democracy to flourish, it must confront the rage within and rebuild what it means to be patriotic.