How do we process speech, taking small features of the sounds emitted from one person and somehow finding meaning in them? Psycholinguistics seeks to illuminate how this process occurs by producing models that break down its steps and elements.

Recognizing spoken words is different than reading because the auditory input reaches the ear over time, and is not processed as a whole. The Cohort model suggests that when we hear the first part of a word, our minds make a list of candidates that start with that sound, called “cohorts.” As we hear more of the word, these candidates are ruled out one by one until only the correct word (the target) is left. In the TRACE model, however, sounds that are consistent with a candidate give it “activation” and when a candidate has been activated enough, we correctly identify it as the word we are hearing. No candidate is ever ruled out entirely, only activated or deactivated based on how consistent it is with the incoming speech sounds.

One way to determine which model is better is to look for rhyme effects. Since the Cohort model (representing the category of feed-forward models) rules out any possible candidates that don’t sound the same as the perceived word at the beginning (words that aren’t cohorts), words that rhyme shouldn’t ever be considered. In TRACE (representing the category of continuous-mapping models), because words that rhyme with the correct word share the same word-end, they should become activated once the end of the word has been heard, and thus briefly considered as candidates. Rhyme effects refer to just that: these candidates (called rhyme competitors) being considered in the processing of spoken words.

Past studies using behavioural methods such as priming and reaction time have failed to find rhyme effects, which is evidence in favour of the Cohort model. But recently, researchers have started using electroencephalogram (EEG; recording the electrical activity on the scalp) and eye tracking methodologies to look at the issue. They have been able to show that people react differently to rhyme competitors than they do competitors that don’t sound at all like the target word, which supports the idea of rhyme effects, and thus the TRACE model.

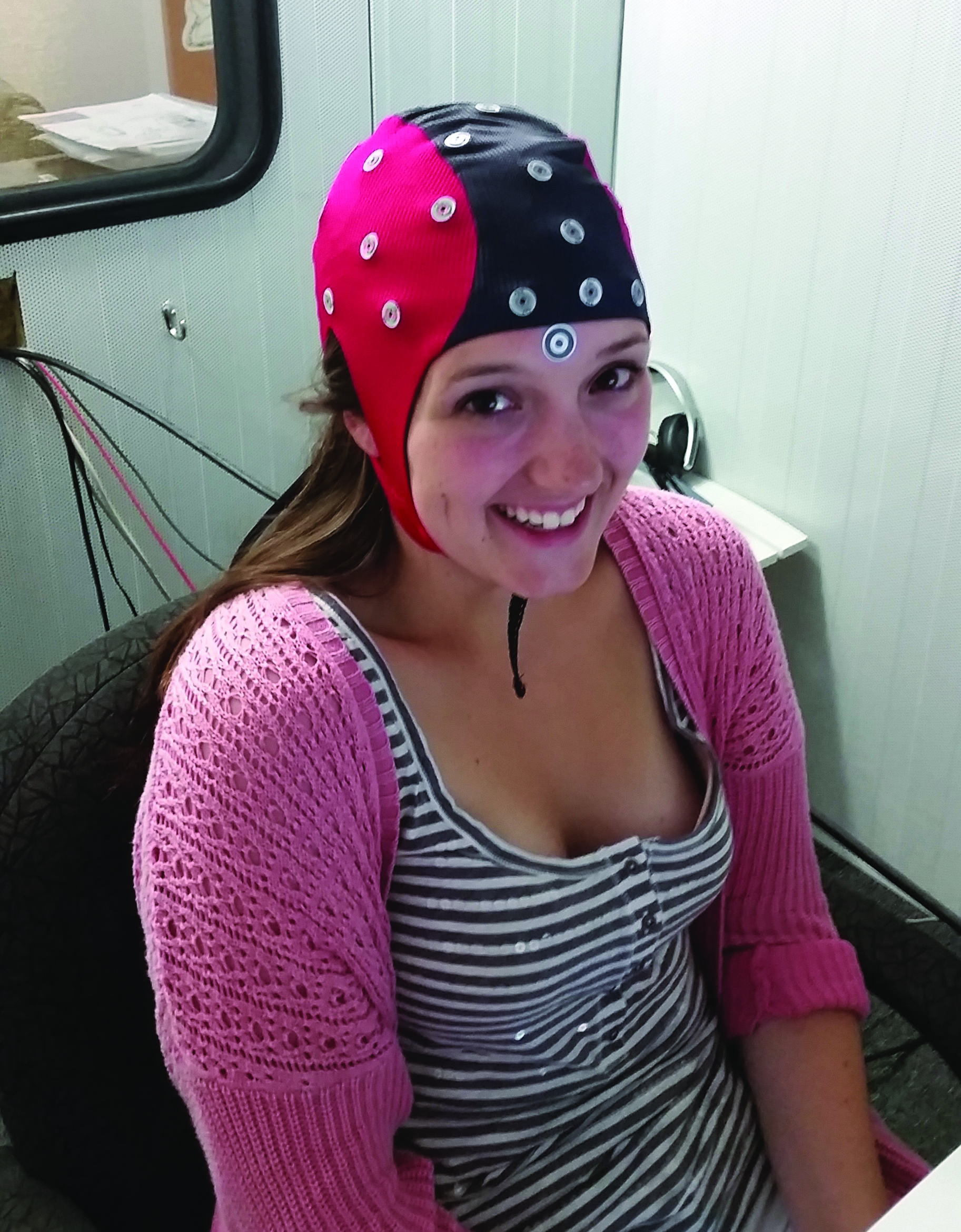

Neither EEG nor eye tracking are perfect, but research in other areas of psychology has been able to use them simultaneously to cover some of their limitations. In order to provide better evidence for rhyme effects, my research recorded scalp activity and eye movements at the same time, so that the scalp activity that occurs directly after a person’s eyes fixate on a picture representing different types of competitors (target word, cohort, rhyme, unrelated) can be analysed. In an audiometric (soundproof) chamber at the Cognitive Neuroscience Laboratory of Acadia University, participants were set up with an EEG cap and calibrated for the eye tracking camera. They were shown sets of four pictures and were instructed to click on the one that matched a spoken word they heard played. Each set of pictures always included a target (e.g. cone) and an unrelated competitor (e.g. fox), and depending on the trial, it might include cohort (e.g. comb) and/or rhyme (e.g. bone) competitors.

The EEG results were inconclusive. Although the overall analysis indicated that there were significant differences between scalp activity following fixations to different competitors, the statistical power was not great enough to fully distinguish between them. However, analysis using more liberal statistical tests did find an indication that fixations to the competitors that started with the same sounds as the spoken word (target and cohort) were different from the competitors that started differently (rhyme and unrelated). The eye tracking results were more definitive, finding that people were significantly more likely to fixate on the rhyme competitor than the unrelated competitor after they heard the last portion of the spoken word. Additionally, people were slower to fixate on the target when a rhyme competitor was present in the picture set, indicating that they were distracted by the rhyming word. Both of these results provide support for rhyme effects.

The combined eye tracking/EEG methodology has a great deal of potential to explore topics in cognition as a whole, not just in psycholinguistics. My current study failed to find the anticipated rhyme effects in the fixation-related EEG signals but it did validate the method by finding alternate effects and identified several limitations and suggestions for future studies using the same technique to take into account. As for the models, evidence is mounting that we process language in a continuous fashion, taking into account all aspects of the word. Models like TRACE are more complicated than alternatives such as Cohort, but they are flexible and can better explain the results seen in the current study and the rest of the literature.

KIDNEY DISEASE: if this type of guy has reversed it everyone can http://renalimpairedfunction.blogspot.com/