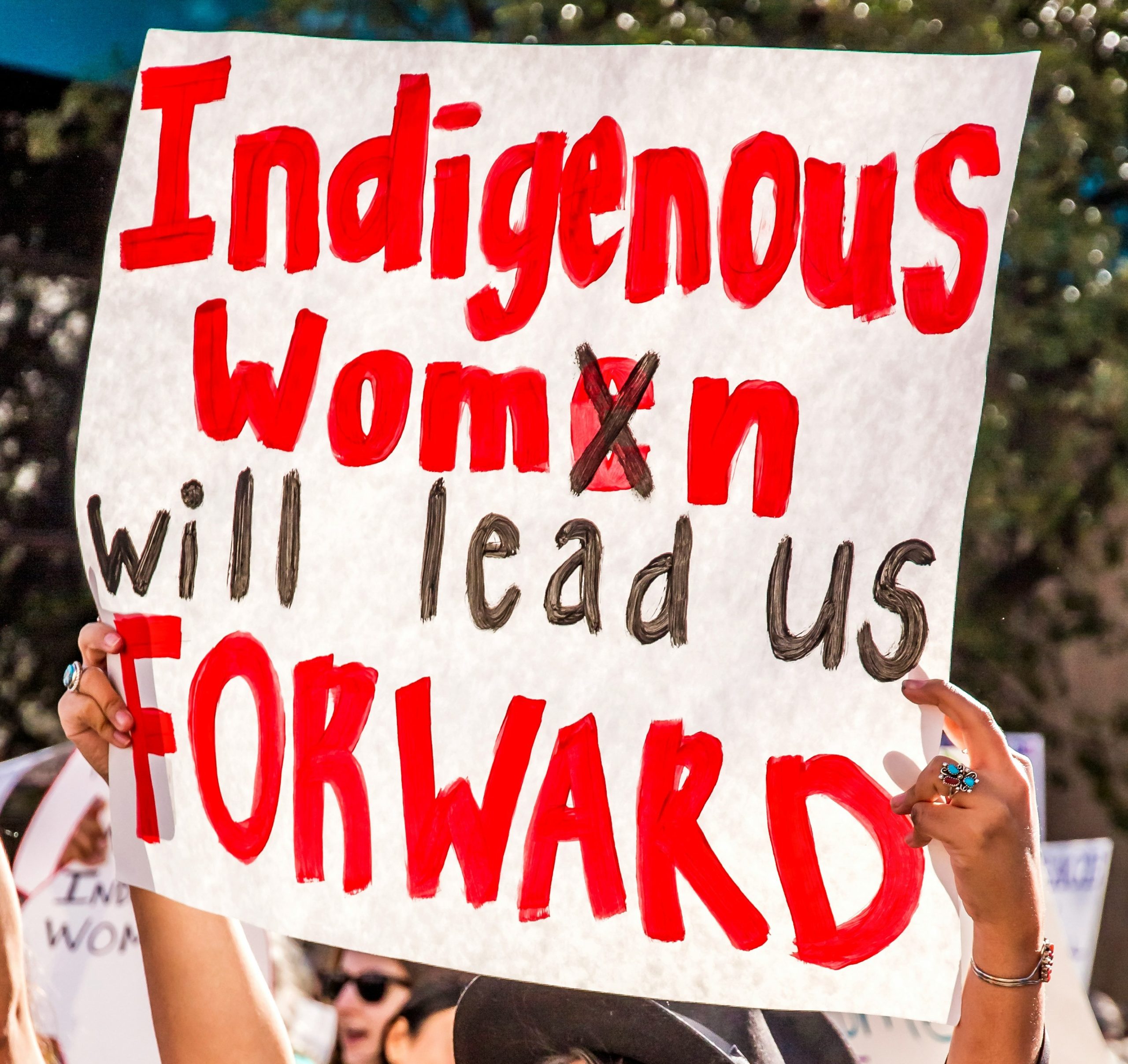

The Consequences of Never being Heard but Always Being Seen for Indigenous Women

Within Canada’s legal system, a startling truth becomes apparent: the simultaneous underrepresentation and overrepresentation of Indigenous women within the system has left them without champions. Although they make up less than 4% of all women in Canada, 50% of the Canadian female prison population are Indigenous women. In British Columbia, where the Indigenous population is notably high, a mere 359 out of 14,000 members of the Law Society identify as Indigenous. This alarming lack of representation not only echoes the boarder issue, but deepens the systemic challenges faced by Indigenous women in their pursuit of justice. It’s a crisis that demands our immediate attention and action.

The problem

The underrepresentation of Indigenous individuals in the legal profession, coupled with their overrepresentation in prison and crime statistics, stems from a web of systemic barriers, with educational obstacles serving as the most pivotal challenge. The trickle-down effect of access to education to the being underrepresented and overrepresented of Indigenous women in the criminal justice system is significant. It starts with limited access to early education, evident in the alarming graduation rates. Less than 63% of Indigenous youth graduate high school, a stark contrast to their non-Indigenous counterparts, who boast a rate just over 91%.

If one beats the high school barrier, the path to post-secondary education, particularly in fields like law, presents its own set of barriers. The University of Toronto’s law school identified a mere 7 Indigenous students of a total enrollment of just over 200 new students per a year. If one is able to beat the education barriers, they are met with their next obstacle, the cost of post-secondary and graduate school education. In Canada the average cost of law school is $20,700 per year. This financial burden becomes especially onerous considering that Indigenous peoples in Canada experience the highest levels of poverty, affecting 1 in 4 individuals.

The consequences of underrepresentation and overrepresentation matter

A diverse and inclusive legal system is crucial for ensuring fair representation and equitable justice. When Indigenous voices are absent from legal institutions, the legal landscape lacks the diverse perspectives and cultural understanding necessary for just and effective decision-making. Secondly, the educational barriers that contribute to this underrepresentation perpetuate a cycle of systemic injustice. Limited access to early education and the financial constraints that impede progress to post-secondary institutions, like law school, reinforce disparities, limiting opportunities for Indigenous individuals. Moreover, the overrepresentation of Indigenous individuals in the criminal justice system is a manifestation of these systemic inequities. Without representation in legal professions, there is a higher likelihood of misinterpretation, bias, and systemic failures that result in disproportionate incarceration rates.

Addressing these issues is not just about rectifying statistical imbalances; it is about rectifying historical injustices and fostering a legal system that truly reflects the diversity and values of the Canadian population. It is an imperative step towards dismantling systemic barriers, promoting justice, and ultimately building a society where Indigenous peoples are empowered, heard, and treated equitably with in the legal framework.

A solution

To address the underrepresentation of Indigenous individuals in the legal profession, a possible strategy involves the implementation of mentorship programs. These types of programs can establish crucial one-on-one connections between seasoned legal professionals and aspiring Indigenous lawyers, aiming to break down barriers and empower the next generation. Specifically addressing the systemic barriers, mentorship provides personalized guidance. This includes navigating financial hurdles and overcoming educational challenges, ensuring that Indigenous mentees receive practical advice to navigate complexities that might otherwise discourage them from pursuing legal careers. Mentorship programs extend beyond mere professional advice; they actively contribute to community building within the legal sphere. By connecting Indigenous students with mentors, these programs foster a supportive community, breaking the isolation that may deter some from entering the legal field. Additionally, mentorship serves as a source of inspiration and gaining role models, exposing mentees to successful Indigenous legal professionals. This type of exposure provides tangible examples of what can be achieved, fostering motivation, and instilling the confidence to pursue a legal career. In 1989, Nova Scotia launched a Black-Nova Scotian and Mi’kmaq mentorship initiative in hopes of achieving a diverse population of lawyers in Nova Scotia. Prior to this initiative zero Black-Nova Scotians and Mi’kmaq graduated from Dalhousie Law School, now there is over 180 Black and Indigenous lawyers.

A compelling example of the impact of representation is found in the journey of British Columbia (B.C.) Family law lawyer Kelly Russ. Inspired by meeting Judge Alfred Scow, the first Indigenous judge in B.C., Russ gained a sense of what was possible during elementary school. Despite spending 13 years in foster care, Russ went on to obtain a law degree and establish his family law firm in West Vancouver, highlighting the powerful influence of representation in breaking down barriers and inspiring success.

Steps forward

It is evident that the underrepresentation of Indigenous women in Canada’s legal system is a multifaceted crisis with deep rooted systemic causes. From limited access to early education, to financial barriers in pursing legal education, these challenges perpetuate a disparity and contribute to the over representation of Indigenous women in the criminal justice system. A solution is urgent; the idea of mentorship could be that first step of change.

It should be everyone’s hope that collective efforts will lead to a legal system that not only rectifies statistical imbalances but also dismantles historical injustices, fostering a society where Indigenous voices are truly heard and empowered within the legal framework. The time for action is now.

Great article!!