Every day that I read the news I am convinced we are moving backwards in time. Daily, headlines reveal how our neighbours to the south are rewinding into a history we had all hoped we had passed. Abortion rights being restricted or revoked, while the insurance coverage for birth control that was previously required by law has also been pushed back. Access to birth control and abortion and fundamental rights for women, and they seem to be disappearing. It is clear that women continue to face barriers when choosing how to control their fertility. How this remains an issue in 2017 is more complex than it seems.

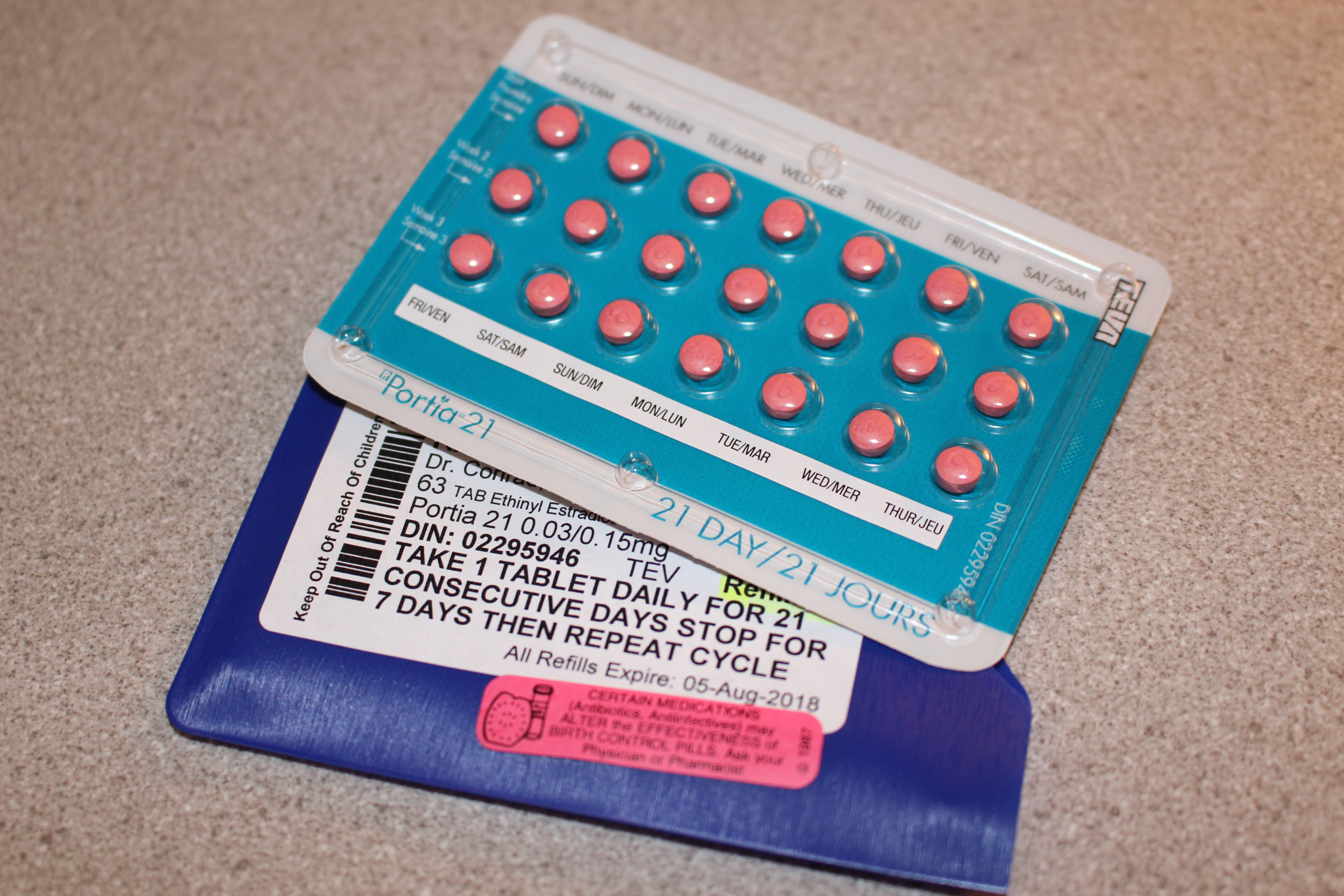

With the overwhelming number of birth control options available today (pills, implants, shots, rings, etc.) women certainly have options. Women have the freedom to choose the right method for their bodies, beliefs and lifestyle; but their freedom to choose seems to disintegrate when it comes to the choice of whether or not to use birth control at all.

When I was interviewing college-aged women about their periods and birth control usage it was overwhelmingly obvious from their stories that they were sold on birth control well before birth, or even, sex was on their radar. Essentially, they were being marketed birth control as a tool for controlling their period, with the supposed added benefit of not having to make any decisions when they finally became sexually active. The implicit assumption is that birth control is both multifunctional and necessary, an assumption that leaves women without non-medical solutions to deal with period difficulties they may be experiencing. Doctors’ are not solely to blame for this state of affairs; even feminist works such as Our Bodies, Ourselves are guilty of encouraging birth control use without discussing the freedom to not use birth control at all.

Women everywhere are faced with challenges when it comes to making these important decisions and the current conditions of our medical system do not make it any easier. Doctors are overworked and have almost no time to read and research best practices regarding birth control advocacy. When they do have time to participate in continuing education, the information they have access to is often from pharmaceutical companies, which push for more and more prescriptions. This leaves doctors with inaccurate information and women without a trusted, unbiased source of advice. Women who refuse to take such biased advice at face value are then forced to handle investigative work themselves, reading through medical information to determine whether or not birth control is a good decision. On top of this, the cost of seeing a doctor, possibly more than once to make a well-informed decision, serves as a barrier for women everywhere.

Women are led to believe that they have more choice today, when really it is just the illusion of choice filtered through the layers of physician and pharmaceutical influence. This paints a bleak picture for women, and highlights the fact that there are still significant barriers to choice for women regarding their reproductive health. While the lack of choice regarding birth control is in no way as traumatizing as coerced sterilization, both situations highlight the fact that women are still not free to exist in the world without inappropriate control exercised upon them. However, as always, they press on. Women are not left without options for navigating the maze of birth control choices. Like the women who came before them, the best way to make decisions is by learning as much as possible, and relying on those around you for their stories, ideas and advice. In a world where women are still not free from unfair and unjust treatment, we must use our knowledge to help each other avoid this treatment.

Kate Dalrymple is completing her graduate work in Sociology at the University of British Columbia. She is an alumni of the Acadia University Sociology department and Women and Gender Studies Department, graduating class of 2016. Some of the research conducted was done so at Acadia, using students as research participants