Some people never meet their grandparents, yet still they remain a topic of discussion at family gatherings or during moments of fond reminiscence. Everyone has heard some stories about their grandparents. Where they came from, who they were, their careers and hobbies. But not me. At least not in any sort of meaningful way. When I was a child, I used to ask my mother questions about her father, my grandfather, to which she would often reply with either very few details or simply: “Your grandfather was not a very kind man.” This was often how these conversations remained. No further questions, no pressure for greater detail. It simply seemed as though my mother just did not wish to talk about it. I spoke to my grandmother plenty, but I never remember hearing my grandmother speak of him.

As I grew older, I would hear parts of conversations or other information which I could piece together to paint a better picture of who my grandfather was. Over the years it became clear why nobody would talk about him. I had asked nearly everyone for details, my aunt, my mother, my father. Eventually I gathered that he was abusive. The family refers to him as Jim even though his full name was Zygmunt Chrominski. He immigrated to Canada from Poland after the Second World War and took residence in Stratford, Ontario.

I knew all these things and yet there were missing details. One would assume that he was just abusive, but there was always something in the voices of those that spoke about him that made me think they felt bad for him.

I was thirteen years old when I first heard that my grandfather had been captured by the Germans in the war. This was something I took pretty lightly- plenty of people were involved in the Second World War and plenty were captured. Sometime after this was the moment, I heard my father say “Auschwitz” when speaking about my grandfather. I had learned about the infamous Nazi death camp in school, I had seen the pictures of the corpses stacked ten feet high in train cars meant for livestock, I had heard about the liquidation of the ghettos. Indeed, it seemed my Grandfather was interned in Auschwitz concentration camp.

Why was he there? When did he get there? What happened to him? How did he survive? I’ve never seriously undertaken an investigation into what happened to my grandfather. For the purpose of recording his story and to satisfy my own curiosity for lost family history I’ve endeavoured to find out exactly what happened to him. Hopefully by the time I’ve completed this journey I’ll know his story from his life in Poland to how he built a life in Canada. In recent years and months more, clues about my grandfather have become available to me. With those small clues and information from my relatives I’m hopeful that Zygmunt’s story will come together.

I was first able to learn the exact date of his birth. He was born in Warsaw, Poland on September 26th, 1922. This meant that the combined forces of Germany and the Soviet Union completed their invasion of his country shortly after his seventeenth birthday. This is where the clues about my grandfather dry up.

Many often ask if I’m Jewish after I tell them that my grandfather was interned in Auschwitz. To my knowledge, I’m not Jewish and it’s essential to our understanding of the Holocaust that we recognize it was not only Jews that were murdered by the Nazi regime. Prisoners of war, members of the LGBTQ community, or people of “undesirable” ethnic descent were also killed by the Nazis. This means that Russians, Ukrainians, and Polish people were also interned in Auschwitz. It is unclear what my grandfather’s wartime life was like. However, after speaking with family there are some conclusions I’ve been able to draw.

My grandfather lived in Warsaw before the war, where he was born. He may have been involved in the Polish Resistance Army or he might have spoken out against the Nazis. The problem with compiling my grandfather’s story is that there are few remaining family sources. My grandmother passed away some years ago and only heard about my grandfather’s time in Auschwitz once. It is possible that the specifics of his camp life died with her.

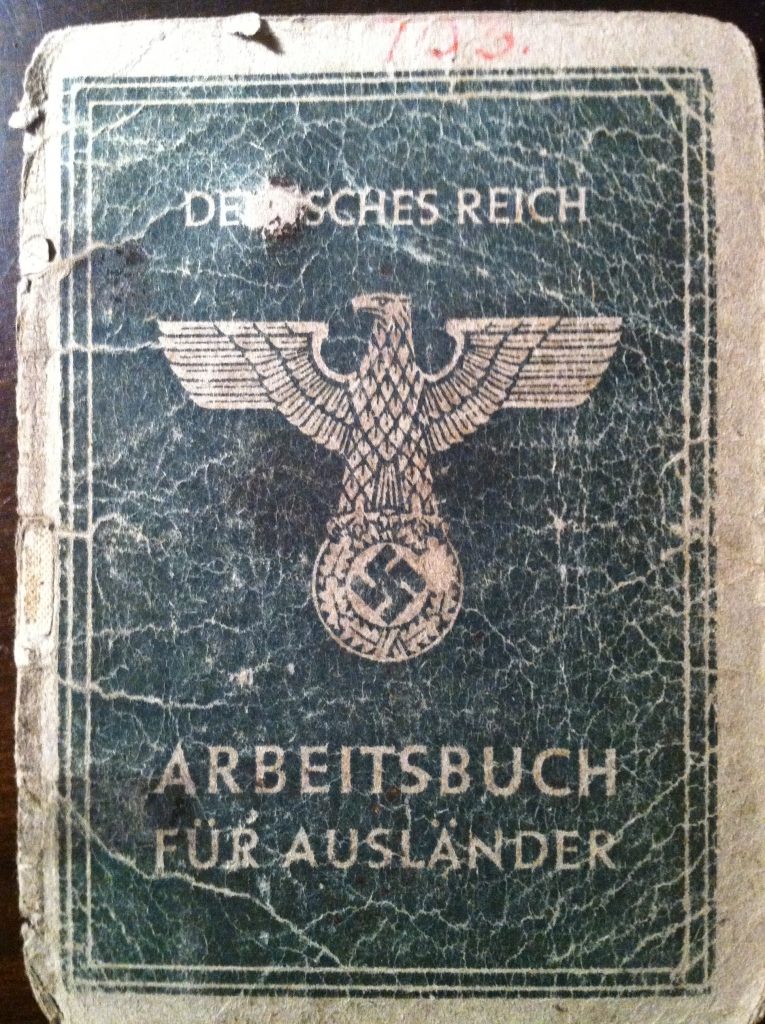

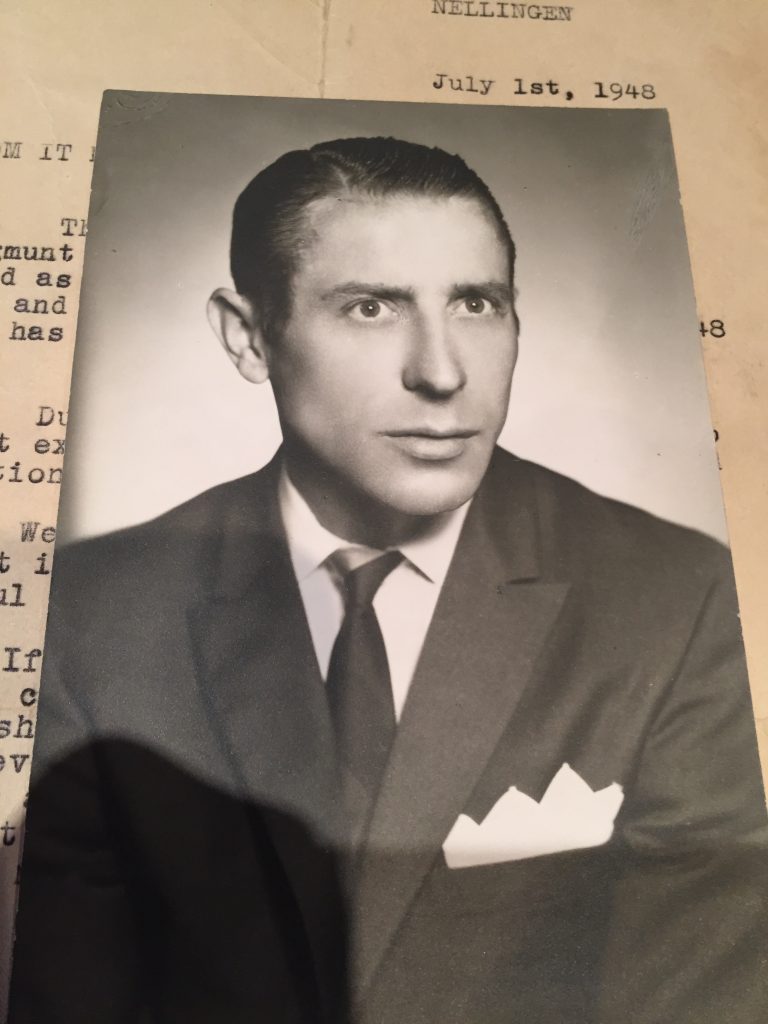

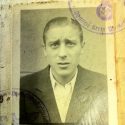

The details available about my grandfather increased only slightly after my grandmother’s passing. In a plastic bag buried in a shoebox in my grandmother’s closet was a tattered book the size of a passport. Although faded, one could still make out the imperial eagle perched on a swastika. Underneath it reads “Arbeitsbuch Fur Auslander” which translates roughly to “Workbook for immigrants.” Contained within this book are the pages which identify who he was, and it includes a picture of him likely taken at a work camp. Below is that picture.

The book provides some information about his work during the war. This was something that most occupied people were issued. The particular papers I have list an ordinance of May 1943 as the wartime law under which it was issued. This led me to believe his was given to him at or after that time.

Until four weeks ago these few details and this one document were all I had to go on. After asking family some questions I received a call from my mother. Inspired by my interest she had done some digging around in some of my grandmother’s old documents. What was uncovered makes for quite a tale. Contained in more than a dozen documents ranging from handwritten letters to government documents is something of an autobiography. Some of the details I had learned were correct, but the truly harrowing parts of his story were not available until recently. What follows is my grandfather’s story from his birth through the war until he reached Canada.

Zygmunt Chrominski was born in Warsaw, Poland on September 26th, 1922. He successfully finished public school in 1935 shortly after Adolf Hitler had seized power of Germany. From 1935 until 1937 Zygmunt attended high school. This was followed by an apprenticeship from 1937 through 1941 during which Poland had been invaded and occupied by Nazi Germany. According to a brief autobiography, because he was a Polish student opposed to German occupation, he was arrested on Skaryszewska Street, Warsaw in May of 1941. From there he was transferred to Szucha Avenue.

During the war Szucha Avenue was closed to Poles. It’s a place locals would have avoided given that it was home to the Gestapo and SS Political Crimes Division and where Polish patriots and resistance fighters were jailed. Today the site is home to the Mausoleum of Struggle and Martyrdom. After this, Zygmunt was transferred to Pawiak Prison. During Nazi occupation Pawiak was part of the journey to various death camps for members of the Home Army or political prisoners. Unfortunately, this was not his final destination but the first of several.

From Pawiak my grandfather was transferred to a coal mine in or around Leipzig, Germany. These were the types of destinations for many war prisoners deemed able to work. He was sent to the area on May 7th, 1941. After a short time near Leipzig he was transferred to another mine near Weisenfels where, according to him, he suffered serious injury to his back and knee. During this time, he was hospitalized the records of which were lost.

On the 20th of February 1942 he managed to escape the work camp he was at in order to return to Poland. A few days after his escape he was captured in Warsaw and sent to Auschwitz.

Auschwitz was where my grandfather was sent to be exterminated. Again, this was not the end of his journey. After a few months in Auschwitz he was transferred to a labour camp that was staffed for Allgemeine Elektricitäts-Gesellschaft (German for General Electric Company), a sub-camp of Auschwitz. After working at the AEG labour camp, he was sent to a place known as Haale, where warplane parts were produced. As a skilled labourer he was in particular demand for metalworking and industrial tasks. After producing parts for the German war machine for some time he was transferred yet again. However, this time he was not sent to a coal mine or an industrial compound.

This is when he is sent to Torgau. During the war this area was home to a notorious Nazi prison. At this place according to his writing he was, “subjected to brutal interrogations and beatings beyond human credibility.” The final camp my grandfather was sent to was yet another coal mine. From November 12th, 1942 my grandfather remained at this unknown coal mining camp. On the 12th of April 1945 after almost five years in various Nazi prisons and death camps he was liberated by American troops. He had survived. The details of the liberation would lead me to believe that his final camp was a subcamp of the Buchenwald concentration facility.

With so much of his country having been destroyed by the war and no home to go back to, my grandfather had nowhere to go. One can only imagine the joy of freedom being tainted by the realization that there was nothing that remained of his previous life. Following his liberation, he was employed by the United States Army Service Company tasked with administering the newly freed areas of Eastern Europe. He worked with the US Army all while living in a displaced persons camp. It was at this refugee camp that he met my grandmother Eugenia. Presumably, they wanted to build a life together but circumstances at the time made it too difficult to continue in what was once their home countries.

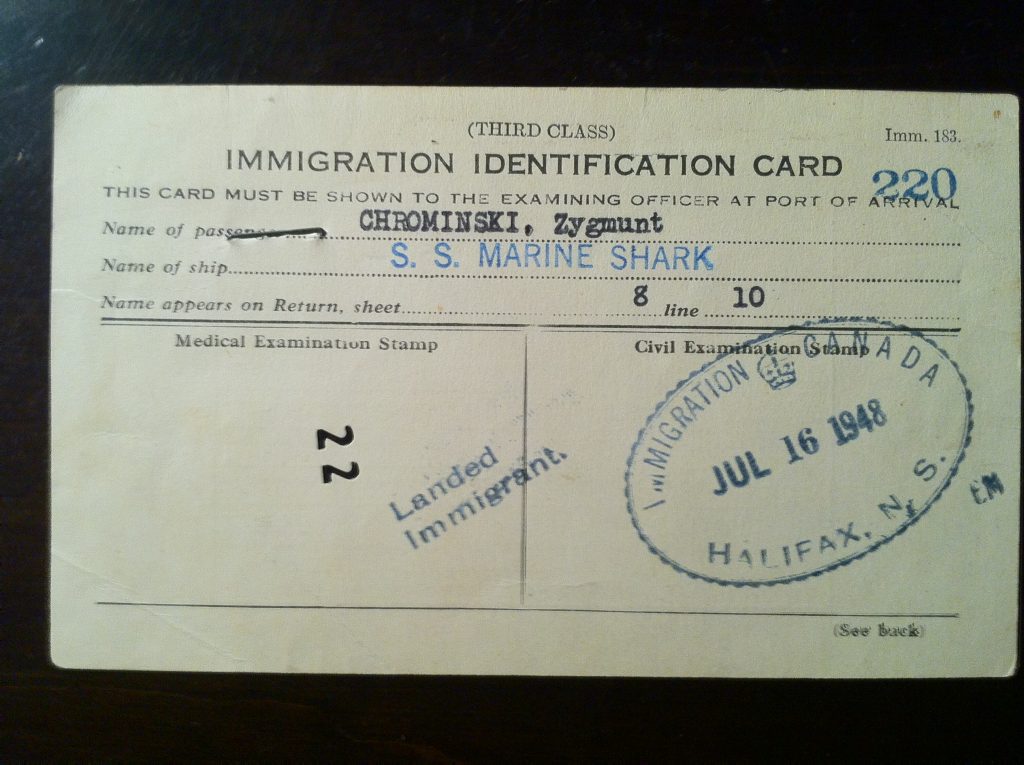

Travelling in third class on the S.S. Marine Shark my grandfather was the first of my mother’s family to make it to Canada. On July 16th, 1948 Zygmunt arrived in Halifax. The horrors of the war were over and thousands of miles away.

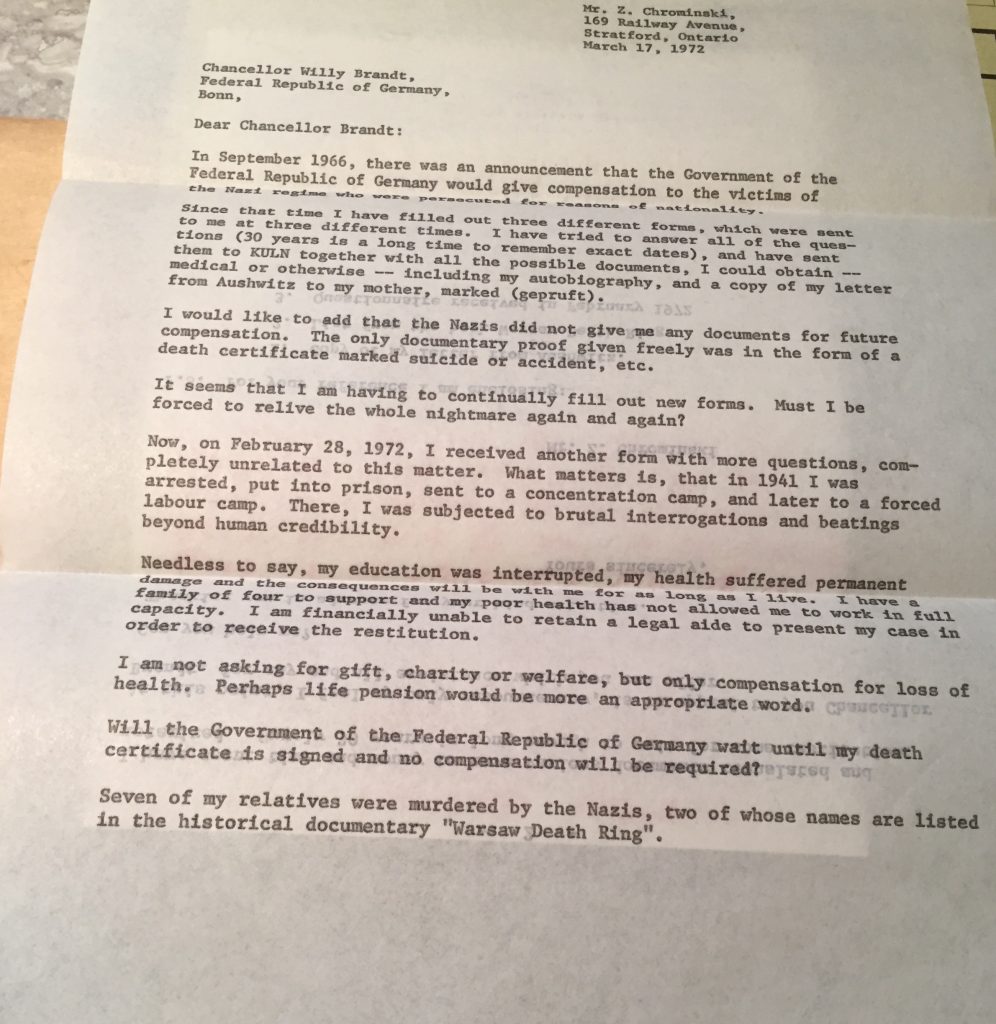

He began again by establishing a life for himself and his new family in Stratford, Ontario. He worked hard over the years as a tool and die maker, fathered three girls and built a home. My grandparents fought almost continuously for reparations from the German government for what my grandfather experienced during the conflict. In letters written years later it is clear that the evils of the Holocaust haunted him forever.

Dated March 17th, 1972 nearly three decades after the end of the war he wrote a letter to Willy Brandt, the Chancellor of Germany requesting assistance. In it he writes, “It seems that I am having to continually fill out new forms. Must I be forced to relive the whole nightmare again and again?” The letter also revealed family I never knew I had. Part of the letter reads: “Seven of my relatives were murdered by the Nazis, two of whose names are listed in the historical documentary ‘Warsaw Death Ring.’” I was able to find the book he had referenced all those years ago. Contained within it is the story of my two relatives. Czeslaw Chrominski was sent to a death camp and Jozef Chrominski was executed and buried in a mass grave outside Warsaw.

Years ago, I travelled to Poland to see my grandfather’s death camp. What I saw there was only what remained of the camp after decades, but it was clear that the horrors that occurred there were something indescribable. One of the things I remember was a room filled to the ceiling with shoes. They were the shoes of those that the Nazi regime had murdered. The sheer number was incalculable.

My grandfather’s story ends on October 14th, 1978. He died as a result of an accident in his home. He never saw the reparations promised to him by the German government. In a letter addressed to German government officials my grandmother wrote: “I intend to give the story of his struggle in Germany, during the Nazis and after, to our newspapers. Send his file to me… What is one more or less file on a dead man when you have killed millions”.

Before I began writing this piece, I assumed that his story was like that of any other Holocaust survivor. What I’ve learned while writing and researching is that every story is never what it appears to be at face value. I became acquainted with someone that I’ve never known, which was quite a privilege.

As someone studying politics, I wonder what my grandfather would think of the current state of affairs. I also find myself preoccupied by what he would think of my political beliefs. What I have learned is that the suffering caused by violent conflict is something that positions itself forever in the minds of those that experience it. Zygmunt spent years reading about the war in an effort to identify those who perpetrated the crimes he witnessed, he never came to any conclusions. The permanent disability caused by the abuses he suffered resulted in Zygmunt never being able to enjoy his life or participate fully in work. Although he survived the war his life must have been an unimaginable nightmare. It’s my sincerest hope that I have done justice to a story that’s never been told.

I would tell readers to investigate their family histories. Resigning stories like these to the past would be tragic. It’s always worth learning about the past especially a past that is so personal. We can never hope to understand the actual damage of the Holocaust but the least we can do is ensure stories like these are heard.

Dedicated to:

Zygmunt Chromiński (1922 – 1978)

Czeslaw Chrominski (November 20th, 1919 – June 20th, 1940)

Jozef Chrominski (May 30th, 1914 – September 17th, 1940)

Christopher Vanderburgh is a fifth year (Honours) Politics student and Features Editor of The Athenaeum

Comments

One response to “Beyond Human Credibility: My Grandfather’s Journey through Auschwitz”

Christopher I cant say whether your Grand father would share your views but I

know he would be proud of you. I grew up with your Mom and never knew this story. I knew there was a harshness to your Grandfather but there was a kindness as well. He often went to St Laurence market on Saturdays in his bright red Beetle and many times would gift me with a fresh bagel and a piece of cake on his return.

Very well written.